Biofouling on ship hulls causes economic and environmental harm

Unchecked biofouling increases drag and degrades hull integrity, and is a major vector for the spread of invasive species

Details

Core information and root causes

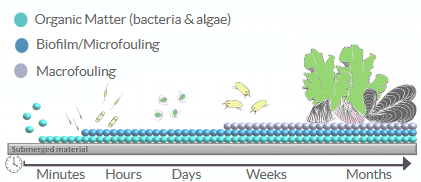

“Biofouling” is the growth of aquatic species like algae, barnacles, and muscles on ship hulls and other infrastructure. “Light fouling” of bacteria and other microorganisms begins almost immediately after an object encounters water, and over time larger organisms take hold (“hard fouling”). Without prevention and management, biofouling leads to a host of economic, environmental, and operational problems. In the context of operational overhead alone, the additional energy required to overcome the drag caused by biofouling is estimated to cost the industry between $10-30 billion in fuel costs per year.1 2

Scope of problem

To comprehend the scale of biofouling in the marine industry the available surface area can be approximated. Between 1999 and 2013, about 120,000 vessels above 100 gross tons were registered as active. Their estimated surface area of 571 km2, demonstrates that surfaces equivalent to the total land area of France require protection3

Factors impacting the rate and degree of fouling

From the International Maritime Organization (IMO)’s guide to biofouling:

- design and construction, particularly the number, location and design of niche areas (e.g. sea chests, bow thrusters, hull appendages and protrusions, etc.);

- specific operating profiles, including parameters such as operating speeds, ratio of time underway compared with time alongside, moored or at anchor, and where the ship is located when not in use (e.g. open anchorage or estuarine port);

- places visited and trading routes (e.g. depending on water temperature and salinity, abundance of fouling organisms, etc.); and

- maintenance history, including the type, age and condition of any anti-fouling coating, installation and operation of anti-fouling systems and dry-docking/slipping and hull cleaning practices.

Why now?

As sea temperatures rise, the scope and scale of issues associated with biofouling will increase as well.

In lab tests for which seawater was warmed 3.5°C above today's average—a scenario that represents water temperatures expected in the year 2100—organisms in a typical community of hull-clinging creatures grew twice as fast as they do under today's conditions. They not only grow more quickly in the warmer water but also grew to form thicker layers4

Impact

Market, people, and economic impacts

Economic Cost

Fuel cost

Fuel Consumption due to increased drag (up to 34% additional drag from biofouling due to increased hull roughness); additional drag forces require up to 86% additional shaft power.5 3

According to one study, the U.S. shipping industry spends more than $36 billion each year in added fuel costs to overcome the drag induced by clinging marine life or for anti-fouling paint that prevents that life from hitching a ride in the first place.4

Cost of treating & managing biofoul

the cost to regularly scrape a hull smooth… costs approximately $4.50 for every square foot of hull surface.4

Hull integrity and asset lifetime

Biofouling marine organisms such as invertebrates promote microbially influenced corrosion of metal structures. Hulls, marine equipment, and offshore vessels are mostly made of steel or aluminum. Even though these materials have excellent corrosion resistance, biofouling organisms such as barnacles colonize their surfaces and compromise their resistance integrity.

Repairing corroded hulls and other surfaces is costly in terms of repair costs and lost business. Additionally, underwater repair for equipment such as drilling rigs is risky and time intensive. In a worst-case scenario, excessive corrosion that goes unrepaired for a long time can cause hull leakages and potentially ground your vessel. 6

Environmental Impact

Studies suggest that light biofouling can cause an additional 20-25% in GHG emissions relative to a clean vessel, with hard biofouling (organisms like barnacles or tubeworms that accumulate in later phases) contributing up to an additional 55% in GHG emissions. Maritime fuel use in shipping accounts for about 2–3% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, roughly 1 billion tons of CO2 annually7. The carbon intensity of biofouling is higher than most countries' annual emissions. Managing it effectively is especially important given the expansion of global trade; Climateworks projects that international shipping emissions could rise to 17% or more of global GHG by 2050.

Efforts

Current initiatives and solutions

Regulatory:

R&D

Pilots & Test Facilities

Opportunities for Philanthropy

- ClimateWorks might investigate incorporating biofouling into its Maritime Shipping program.

Approach

Strategic approach and implementation plan

Preventative

Anti-fouling (AF) Coatings

Antifouling coatings contain biocides that prevent the settlement of organisms like algae and mollusks.

Context on the state of the market, from the 2023 report “Marine biofouling and the role of biocidal coatings in balancing environmental impacts”:

Today the commercial market for hull coating solutions is largely dominated by biocidal antifouling (AF) coatings. In 2011, approximately 94% of the applied coatings were reported to be biocidal AF coatings (Lindholdt et al. Citation2015). Three years later, their market share decreased to 90% indicating the shift in the industry towards the new technologies (Ciriminna et al. Citation2015). Despite that, AF coatings are still widespread products whose performance rely on the controlled release of biocidal molecules through diffusion and matrix degradation

Considerations

- Different anti-fouling coatings may be applied in response to specific conditions, limiting the efficacy across changing circumstances

The issue with antifouling coatings is that they must provide protection against a broad diversity of fouling organisms in vastly different climates. Modern antifouling coatings are typically tailored to specific use cases, such as long idle periods, vessel speeds, and trade regions, taking water temperature and main fouling organisms into consideration. Upon deviation from the originally specified trade route, significant fouling or coating deterioration may occur.3

- Coatings may have negative effects on marine life through leaching and bioaccumulation

These compounds slowly "leach" into the sea water, preventing barnacles and other marine life from attaching to the ship. But studies have shown that these compounds persist in the water, killing sealife, harming the environment and entering the food chain. One of the most effective biocides for use in anti-fouling paints, developed in the 1960s, was the organotin compound tributyltin (TBT), which has been proven to cause deformations in oysters and sex changes in whelks, as well as longer-term effects due to its persistence and bioaccumulation.8

- Tolerance & Adaptation

With the wide use of copper based coatings, many biofouling organisms are beginning to demonstrate tolerance such as bryozoans and barnacles9

Fouling release (FR) Coatings

Fouling release coatings reduce the attachment strength of organisms, making them easier to remove through cleaning or regular motion of the ship.9

UV-C Lighting

Use of UV-C lights is promising but still in the research phase of its development

UV-C light operates at short wavelengths (240 to 280 nm) and is highly energetic, making it dangerous to human tissues yet nontoxic to the environment. Although UV-C light is naturally emitted by the sun, it is fully absorbed by the atmosphere. Organisms’ DNA and RNA absorb this short-wavelength energy, altering their genetic structure and rendering them unable to reproduce. Consequently, bacteria and other microorganisms are deactivated, leading to disinfection of the surface where UV-C light is concentrated10

There is noteworthy progress in development of UV-C panels with low power LEDs embedded in a silicone matrix for the application on exterior hull surfaces. Until this technology is applicable for large structures, their use is at least practical for smaller submerged components and sensors11

Testing silicone tiles embedded with UV-Cs:

40–90% reduction in biofouling coverage on silicone tiles embedded with UV-emitting LEDs, even as the LED output waned (after ~8000 h)12

Biofilm-resistant glass (useful especially for sensors and windows)

A group of researchers led by University of Massachusetts Amherst engineers have created ultraviolet (UV) rays-emitting glass that can reduce 98% of biofilm from growing on surfaces in underwater environments13

Ultrasound

ultrasound-based technologies are effective in preventing biofouling by creating cavitation bubbles. While there are concerns about their application in open waters due to noise levels that impact other marine organisms, it can be an effective option for land-based operations11

Hull Design Topology to minimize fouling

Predictive Maintenance

Given parameters that impact fouling, provide a customized maintenance schedule that minimizes cost and disruption

Since the introduction of the automated identification system (AIS) based on terrestrial (2007) and satellite tracking (2013), data from a broad variety of vessels is accessible. Particularly trade routes, vessel speed, idle times, and water conditions are of interest to predict the fouling status. Additionally, ISO 19030 introduced in 2016, allows continuous monitoring of the performance of vessels to creates important insight on the fouling status.

With these tools on hand, the top paint companies started to expand their product line with online monitoring tools, which help to predict biofouling and guarantee the performance of their antifouling coatings. For example, AkzoNobel’s Intertrac HullCare as well as Chugoku’s monitoring & Analysis Program (MAP) harness the power of big data collected by their software. Combined with ISO19030 these tools provide guidance for maintenance advice. Jotun also offers a hull performance solution (HullKeeper), which claims optimised hull performance regardless of the applied coating. The use of the program enables ship operators to take full control of their operations with hull monitoring, fouling risk alerts, inspections and advisory services helping them to identify potential fouling problems. Further, 3rd party companies, such as WE4SEA, entered the market providing competitive online tools for ship monitoring11

Promote the establishment of beneficial organisms9

Reactive

Mechanical Cleaning (In-Water)

ROV-based cleaning See companies listed in Table 2 for an overview of current approaches employed by ROV solutions

Considerations:

In-water cleaning is an important measure to remove biofouling from the hull and niche areas, but may physically damage the anti-fouling coatings, shorten coating service lifetime and release harmful waste substances and invasive aquatic species into the environment.14

Regulatory

Develop a legally binding international framework for control and management of ship biofouling

The Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC) is working on this framework, and expects to publish it in 2029

The development of mandatory requirements will shift biofouling management from voluntary guidelines to enforceable international regulations and provide greater legal certainty in managing biofouling risks. The new output was assigned to the PPR Sub-Committee as the associated organ, with four sessions needed to complete the item; based on this, by the eighty-ninth session of the MEPC (mid-2029) the PPR Sub-Committee would provide a finalized draft legal framework and recommendations on the way forward15

Port incentives for exceeding standards

Singapore has experimented with incentives for ships that exceed the minimum requirements16

Forecast

Future scenarios and predictions

Future Scenarios

Three potential futures for this bottleneck based on current trends and possible developments.

Scenario 1

AI-Nudged Biofouling Optimization

WHAT CHANGES:

Fleet operators adopt predictive maintenance and AI-augmented monitoring tools at scale, optimizing anti-fouling schedules and vessel routes to reduce drag, cost, and emissions.

WHY IT HAPPENS:

- Expansion of ISO 19030 adoption and third-party data layers drive performance-based fleet operations.

- Lower cost of hull sensors and real-time performance monitoring.

- Ports and insurers begin to offer dynamic incentives for low-drag, clean-hull fleets.

WHAT IT MEANS:

Biofouling becomes a performance KPI rather than a maintenance liability. Large operators integrate predictive antifouling into their ESG reports, and pressure mounts for laggards to comply. Compliance becomes cost-saving.

WHEN:

- Early signs: 2026–2028

- Full effect: 2030–2033

LIKELIHOOD: HIGH

Technological components exist; the barrier is more behavioral than technical, and ESG-linked incentives are aligning across sectors.

Scenario Type: "SHIFTS"

Timeframe: "MEDIUM TERM"

Scenario 2

Fouling Credits and Maritime Climate Finance

WHAT CHANGES:

Biofouling becomes a verifiable emissions metric in carbon accounting frameworks, triggering the emergence of "fouling credits" or financing penalties.

WHY IT HAPPENS:

- Maritime Scope 1 emissions face tightening under revised IMO climate targets.

- Fouling-linked GHG emissions reach parity with some small nation-state carbon footprints.

- ESG investors and insurers pressure carriers to show clean-hull practices or face financing penalties.

WHAT IT MEANS:

Shipping finance includes due diligence on biofouling control. A ship’s hull status affects its credit rate, similar to how building efficiency affects real estate lending. “Fouling audits” emerge as part of port entry requirements or green lending protocols.

WHEN:

- Early signs: 2027–2029

- Full effect: 2032–2035

LIKELIHOOD: MEDIUM

Some movement exists in emissions-linked financial products, but the standardization of fouling as a metric is still under development. Watch the MEPC legal framework progress.

Scenario Type: "SHIFTS"

Timeframe: "LONG TERM"

Scenario 3

Anti-fouling Backlash and Policy Reversal

WHAT CHANGES:

Massive biocide contamination events or marine biodiversity collapses (e.g., near coral reefs or estuarine ports) spark a regulatory crackdown on antifouling compounds.

WHY IT HAPPENS:

- A major investigative exposé links biocidal antifouling coatings to ecosystem collapse.

- High-profile class-action lawsuits from fisheries or coastal nations.

- UN treaty mechanisms or regional bans cascade into global restrictions.

WHAT IT MEANS:

Widespread withdrawal of high-performance antifouling options leads to resurgence in hard fouling. Ships face steep cleaning costs and operational delays. Ports tighten restrictions on in-water hull cleaning due to invasive species concerns, compounding the problem.

WHEN:

- Early signs: 2026–2028

- Full effect: 2029–2031

LIKELIHOOD: LOW

Strong lobbying from the coatings industry and lack of ready substitutes reduce the likelihood, but high-impact ecological events could trigger a shift.

Scenario Type: "MULTIPLIES"

Timeframe: "MEDIUM TERM"

Cross Impact Analysis

Key trends across all scenarios:

- Climate-linked financing mechanisms increasingly influence operational behavior.

- Sensor-enabled digital twins and predictive maintenance emerge as universal enablers.

- Regulatory and ESG frameworks evolve to internalize environmental externalities like fouling.

Early warning signs to watch:

- Pilots of fouling-as-a-service insurance or credits.

- Uptake of ISO 19030 in regional port authorities.

- Public backlash against copper or biocide accumulation in marine zones.

Bottleneck Resilience Evaluation

The biofouling bottleneck is moderately resilient—it shifts in most plausible futures rather than disappearing entirely. Addressing it unlocks substantial climate and cost benefits but also introduces new complexities in marine coatings regulation and data standardization. Solving it could become a keystone for maritime decarbonization and ESG financing, warranting strategic prioritization.